Know your (film)

zines!

Cinedome is a collaborative film zine about pirating, the obscure, the experimental, and the allround passion for cinema.

For its third edition I got the chance to write about an interesting subject... Zines!

Read my article below and check out Cinedome on its website here! In it you can also read my interview with Maximilium Luc Proctor, founder of UltraDogme.

![]()

We’re not the first and we won’t be the last. Film zines. What are they? If you read the first two editions of Cinedome, you can figure it out. But if not, here’s a little recap.

Where film magazines are professionally published with a large quantity of prints, film zines are self-published, small-scale magazines that focus on a particular aspect of film culture, film making, or film history. Usually, like in our case, they are created by cinephiles, or independent filmmakers who are passionate about cinema and want to share their knowledge, opinions, and creative work with a like-minded community.

Film zines have a long history, dating back to the 1930s, when fans of science fiction and horror films started creating their own publications to discuss the works they loved and hated. Fan letters send to Hugo Gernsback’s science-fiction magazine ‘Amazing Stories’ would be published with sender address and all, which took out the middle man, eventually leading fans to start their own zines together like ‘The Comet.’

In the 1960s and 1970s, film zines became a popular medium for avant-garde filmmakers and experimental artists who wanted to challenge the dominant Hollywood narrative and explore alternative forms of storytelling.

Today, the DIY culture of film zines is bigger than ever, since an online landscape makes it easier to create, publish, and access zines.

To clarify, we’re not talking Sight & Sound or Cahiers du Cinéma in this article, since those are more traditional magazines, but we will make some detours to the art zines and self-published newspapers. Many film zines eventually turned in -to an extend- professional magazines, but we’re discussing them as zines, since that’s what they started out as.

With that out of the way, let’s take a trip down memory lane and discuss the ones that paved the way, the ones that came before our Cinedome.

![]()

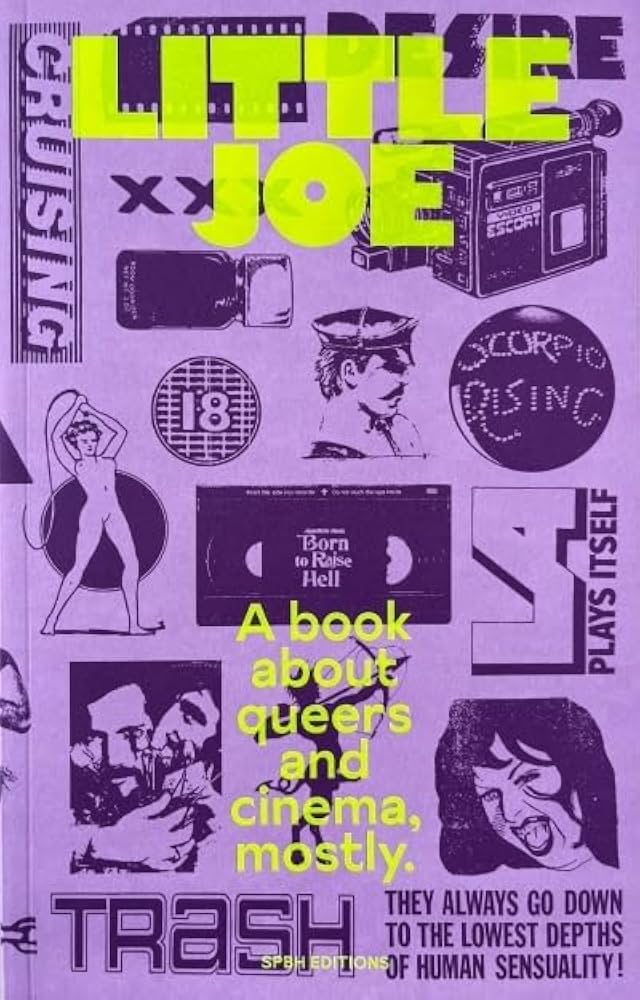

LITTLE JOE

Let’s start with a recent one that is an example of how to do it right.

In 2010, filmmaker and poster artist Sam Ashby brought a gem of a zine in the world with the first edition of Little Joe. For the title, Ashby got inspired by his childhood crush: Warhol superstar Joe Dallesandro, a fitting character for a quite sensual zine.

The six editions of the zine primarily discuss queer history in cinema and are filled with essays, artwork, in depth interviews, and even comics. You might think, ‘six editions since 2010 is not a lot,’ but I would argue Little Joe is much more than just any zine, as it’s more like a series of books. The first edition was 80 pages long, while the sixth one, that came out in 2021 after a six-year hiatus, is a staggering 192 pages long. The zine is carefully curated and designed and there is a very limited amount of prints of each edition.

If the thought of Little Joe makes you tingle, I’d suggest to buy a copy of Little Joe 6 right now, you for sure won’t regret it.

![]()

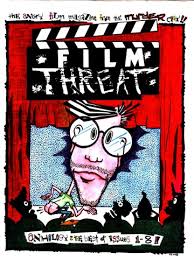

Film Threat

Yes, that website with all the payed reviews and the rants about Hollywood started out as a zine.

In 1985 Chris Gore envisioned a movie magazine with a punk-rock attitude - A common trait of zines we will discuss later on. During his time on Wayne State University, Chris met Andre Seewood and together they started out making 500 copies of their first 6-page-long zine using Xerography and spreading them around campus. It would include jokes, parodies, reviews and essays. These Xerography copies lasted for eight editions, afterwards Chris started out scamming copy shops into copying more professional looking magazines of Film Threat. It was only in the mid-90’s when Film Threat launched its website.

The punk story of the birth of film thread is a fun deep dive, best listened to in interviews with Chris Gore himself.

![]()

Bright Lights Film Journal

With a very early interested in world-, experimental-, underground-, exploitation- and marginal cinema, Gary Morris published his first zine in 1967 at the age of 16. After becoming a typesetter post-college, he soon teamed up with his brother who was a lithographer, and a group of East Coast auteurist friends, including Howard Mandelbaum, Roger McNiven, Robert Smith, and Jeff Wise. The group had experience in publishing zines themselves and had access to a large archive of movie stills. Together they birthed the first issue of Bright Lights in 1974 as an American counterpart to the European Cahiers du Cinema.

For six years the zine appeared quarterly and combined popular and academic styles of writing and included humor and politics and everything in between. Afterwards it existed on and off, until in 1996 it transitioned to the online landscape as many zines did in the time. It’s still going strong today, so it’s definitely one to look an eye out for when you’re interested in reading more zines.

![]()

Camera Obscura

Camera Obscura was first published in 1976 by a group of feminist film scholars and activists, including Claire Johnston, Claire Wilbur, and B. Ruby Rich. The zine was printed using a photocopier, like many of the zines at the time. The contents were focused on feminist film theory and it challenged cinema from the feminist perspective. This included writings about women’s representation on screen while pledging for inclusivity, the politics behind productions, and the attitude towards gender and sexuality.

Eventually Camera Obscura evolved into an academic journal, but to this day it is a key player regarding feminist film studies.

----

New York…

And now, with those four amazing zines out of the way, let’s talk NEW YORK. Punk city. The epicenter of counter culture. The Valhalla of the experiment. The birthplace of many zines throughout the years. A personal favorite I won’t discuss here is ‘Fuck You, A Magazine.’

A punk-rock attitude as a trait of many zines was briefly discussed before, but this is best done in relation to New York. Punk was birthed here in every industry; in music think The New York Dolls and Patti Smith, in art think Andy Warhol, in fashion think Jackie Curtis, and of course in film think Jack Smith, John Wathers, and Kenneth Anger. All these people came together in famous places like Max’s Kansas City, the Factory, and most important for this article: Jonas Mekas’ Filmmakers Co-operative.

Before he turned his loft into the Filmmakers Co-operative in 1962, Mekas already did plenty for the underground film scene. As early as 1954 he published his own zine named Film Culture together with his brother Adolfas. Film Culture first a zine, then of course in time becoming a full fletched magazine running until 1996, was an important print for the underground scene. It explored the experimental and presented awards to independent filmmakers like Stan Brakhage (for The Dead and Prelude, 1962) and Michael Snow (for Wavelength, 1968).

A compilation of articles from the zine can be read in the book ‘Film Culture Reader.’

Afterwards it didn’t stop for Mekas as he had a reappearing column about the independent film scene in the Village Voice since 1958. The Village Voice, somewhat like the East Village Other, is not a zine at all, but I still want to discuss it briefly as more important names had writings about film in this used-to-be-little newspaper.

The Village Voice has a long-standing tradition of film criticism, and was known for its coverage of avant-garde cinema. The earlier mentioned B. Ruby Rich coined the term ‘New Queer Cinema’ in a 1992 article for the Village Voice. It was even reprinted later in Sight and Sound magazine.

From here on the 60’s in New York were a birthplace of many more zines, partly thanks to Mekas and his efforts to celebrate the outcast filmmakers, not only with the Co-operative, but also with the New American Cinema Group, of which the manifesto is a fantastic read. Know your film manifestos would make for another great article, which we might see appear in a next issue of Cinedome.

Anyways, let’s talk more zines, specifically another NY zine in Cineaste!

Cineaste began as a zine in 1967, founded by Gary Crowdus and friends, dissatisfied with mainstream film criticism of the time. Eventually turning into a quarterly magazine, it featured in-depth articles, interviews, and reviews by prominent critics and scholars. It is known to be an important voice for films made by women and people of colour.

Cineaste is still going strong as a magazine and in addition it has a website with extra, free articles, that are definitely worth the read.

Then lastly, another personal favourite zine is The Underground Film Bulletin.

In 1984 Nick Zedd coined the term ‘Cinema of Transgression’ in the Manifesto of the same name, which he published under one of his then many pennames ‘Orion Jeriko’ in his zine ‘ The Underground Film Bulletin.’

Cinema of Transgression talked about filmmakers using shock value and black humor in their films. Besides Zedd himself, filmmakers in the movement include Kembra Pfahler, Jon Moritsugu, and David Wojnarowicz among others. It was a radical zine that embraced violence and sex and championed a DIY approach to filmmaking. The zine was short-lived, as it ended publishing new editions in 1990, but the importance can still be felt in the underground film world today.

Editions of the zine, which have beautiful covers, can be still found online.

-----

Of course there’s plenty more zines to be discussed, as we didn’t even touch on any zines outside of the English language, as well as some more major names from the U.S (at the last moment of writing this I scrapped music zine The Big Takeover). Also, film magazines specifically deserve an article of their own. But here’s where hopefully some reader letters come in, like in the days of Amazing Stories. Wouldn’t it be nice if readers share their favorite zines that could be discussed in the next Cinedome issue? Maybe even an archive of all the ones that came before us can be created, including both zines and magazines, as the line between them can be so thin. And finally, if these zines inspired you to write yourself, why not apply to contribute for Cinedome? Check out how on cinedome.org!

![]()

For its third edition I got the chance to write about an interesting subject... Zines!

Read my article below and check out Cinedome on its website here! In it you can also read my interview with Maximilium Luc Proctor, founder of UltraDogme.

We’re not the first and we won’t be the last. Film zines. What are they? If you read the first two editions of Cinedome, you can figure it out. But if not, here’s a little recap.

Where film magazines are professionally published with a large quantity of prints, film zines are self-published, small-scale magazines that focus on a particular aspect of film culture, film making, or film history. Usually, like in our case, they are created by cinephiles, or independent filmmakers who are passionate about cinema and want to share their knowledge, opinions, and creative work with a like-minded community.

Film zines have a long history, dating back to the 1930s, when fans of science fiction and horror films started creating their own publications to discuss the works they loved and hated. Fan letters send to Hugo Gernsback’s science-fiction magazine ‘Amazing Stories’ would be published with sender address and all, which took out the middle man, eventually leading fans to start their own zines together like ‘The Comet.’

In the 1960s and 1970s, film zines became a popular medium for avant-garde filmmakers and experimental artists who wanted to challenge the dominant Hollywood narrative and explore alternative forms of storytelling.

Today, the DIY culture of film zines is bigger than ever, since an online landscape makes it easier to create, publish, and access zines.

To clarify, we’re not talking Sight & Sound or Cahiers du Cinéma in this article, since those are more traditional magazines, but we will make some detours to the art zines and self-published newspapers. Many film zines eventually turned in -to an extend- professional magazines, but we’re discussing them as zines, since that’s what they started out as.

With that out of the way, let’s take a trip down memory lane and discuss the ones that paved the way, the ones that came before our Cinedome.

LITTLE JOE

Let’s start with a recent one that is an example of how to do it right.

In 2010, filmmaker and poster artist Sam Ashby brought a gem of a zine in the world with the first edition of Little Joe. For the title, Ashby got inspired by his childhood crush: Warhol superstar Joe Dallesandro, a fitting character for a quite sensual zine.

The six editions of the zine primarily discuss queer history in cinema and are filled with essays, artwork, in depth interviews, and even comics. You might think, ‘six editions since 2010 is not a lot,’ but I would argue Little Joe is much more than just any zine, as it’s more like a series of books. The first edition was 80 pages long, while the sixth one, that came out in 2021 after a six-year hiatus, is a staggering 192 pages long. The zine is carefully curated and designed and there is a very limited amount of prints of each edition.

If the thought of Little Joe makes you tingle, I’d suggest to buy a copy of Little Joe 6 right now, you for sure won’t regret it.

Film Threat

Yes, that website with all the payed reviews and the rants about Hollywood started out as a zine.

In 1985 Chris Gore envisioned a movie magazine with a punk-rock attitude - A common trait of zines we will discuss later on. During his time on Wayne State University, Chris met Andre Seewood and together they started out making 500 copies of their first 6-page-long zine using Xerography and spreading them around campus. It would include jokes, parodies, reviews and essays. These Xerography copies lasted for eight editions, afterwards Chris started out scamming copy shops into copying more professional looking magazines of Film Threat. It was only in the mid-90’s when Film Threat launched its website.

The punk story of the birth of film thread is a fun deep dive, best listened to in interviews with Chris Gore himself.

Bright Lights Film Journal

With a very early interested in world-, experimental-, underground-, exploitation- and marginal cinema, Gary Morris published his first zine in 1967 at the age of 16. After becoming a typesetter post-college, he soon teamed up with his brother who was a lithographer, and a group of East Coast auteurist friends, including Howard Mandelbaum, Roger McNiven, Robert Smith, and Jeff Wise. The group had experience in publishing zines themselves and had access to a large archive of movie stills. Together they birthed the first issue of Bright Lights in 1974 as an American counterpart to the European Cahiers du Cinema.

For six years the zine appeared quarterly and combined popular and academic styles of writing and included humor and politics and everything in between. Afterwards it existed on and off, until in 1996 it transitioned to the online landscape as many zines did in the time. It’s still going strong today, so it’s definitely one to look an eye out for when you’re interested in reading more zines.

Camera Obscura

Camera Obscura was first published in 1976 by a group of feminist film scholars and activists, including Claire Johnston, Claire Wilbur, and B. Ruby Rich. The zine was printed using a photocopier, like many of the zines at the time. The contents were focused on feminist film theory and it challenged cinema from the feminist perspective. This included writings about women’s representation on screen while pledging for inclusivity, the politics behind productions, and the attitude towards gender and sexuality.

Eventually Camera Obscura evolved into an academic journal, but to this day it is a key player regarding feminist film studies.

----

New York…

And now, with those four amazing zines out of the way, let’s talk NEW YORK. Punk city. The epicenter of counter culture. The Valhalla of the experiment. The birthplace of many zines throughout the years. A personal favorite I won’t discuss here is ‘Fuck You, A Magazine.’

A punk-rock attitude as a trait of many zines was briefly discussed before, but this is best done in relation to New York. Punk was birthed here in every industry; in music think The New York Dolls and Patti Smith, in art think Andy Warhol, in fashion think Jackie Curtis, and of course in film think Jack Smith, John Wathers, and Kenneth Anger. All these people came together in famous places like Max’s Kansas City, the Factory, and most important for this article: Jonas Mekas’ Filmmakers Co-operative.

Before he turned his loft into the Filmmakers Co-operative in 1962, Mekas already did plenty for the underground film scene. As early as 1954 he published his own zine named Film Culture together with his brother Adolfas. Film Culture first a zine, then of course in time becoming a full fletched magazine running until 1996, was an important print for the underground scene. It explored the experimental and presented awards to independent filmmakers like Stan Brakhage (for The Dead and Prelude, 1962) and Michael Snow (for Wavelength, 1968).

A compilation of articles from the zine can be read in the book ‘Film Culture Reader.’

Afterwards it didn’t stop for Mekas as he had a reappearing column about the independent film scene in the Village Voice since 1958. The Village Voice, somewhat like the East Village Other, is not a zine at all, but I still want to discuss it briefly as more important names had writings about film in this used-to-be-little newspaper.

The Village Voice has a long-standing tradition of film criticism, and was known for its coverage of avant-garde cinema. The earlier mentioned B. Ruby Rich coined the term ‘New Queer Cinema’ in a 1992 article for the Village Voice. It was even reprinted later in Sight and Sound magazine.

From here on the 60’s in New York were a birthplace of many more zines, partly thanks to Mekas and his efforts to celebrate the outcast filmmakers, not only with the Co-operative, but also with the New American Cinema Group, of which the manifesto is a fantastic read. Know your film manifestos would make for another great article, which we might see appear in a next issue of Cinedome.

Anyways, let’s talk more zines, specifically another NY zine in Cineaste!

Cineaste began as a zine in 1967, founded by Gary Crowdus and friends, dissatisfied with mainstream film criticism of the time. Eventually turning into a quarterly magazine, it featured in-depth articles, interviews, and reviews by prominent critics and scholars. It is known to be an important voice for films made by women and people of colour.

Cineaste is still going strong as a magazine and in addition it has a website with extra, free articles, that are definitely worth the read.

Then lastly, another personal favourite zine is The Underground Film Bulletin.

In 1984 Nick Zedd coined the term ‘Cinema of Transgression’ in the Manifesto of the same name, which he published under one of his then many pennames ‘Orion Jeriko’ in his zine ‘ The Underground Film Bulletin.’

Cinema of Transgression talked about filmmakers using shock value and black humor in their films. Besides Zedd himself, filmmakers in the movement include Kembra Pfahler, Jon Moritsugu, and David Wojnarowicz among others. It was a radical zine that embraced violence and sex and championed a DIY approach to filmmaking. The zine was short-lived, as it ended publishing new editions in 1990, but the importance can still be felt in the underground film world today.

Editions of the zine, which have beautiful covers, can be still found online.

-----

Of course there’s plenty more zines to be discussed, as we didn’t even touch on any zines outside of the English language, as well as some more major names from the U.S (at the last moment of writing this I scrapped music zine The Big Takeover). Also, film magazines specifically deserve an article of their own. But here’s where hopefully some reader letters come in, like in the days of Amazing Stories. Wouldn’t it be nice if readers share their favorite zines that could be discussed in the next Cinedome issue? Maybe even an archive of all the ones that came before us can be created, including both zines and magazines, as the line between them can be so thin. And finally, if these zines inspired you to write yourself, why not apply to contribute for Cinedome? Check out how on cinedome.org!